Playdough is one of our Educators’ favourite activities and has been a staple of the Early Childhood Education and Care setting for decades. Why?

Because of the range of developmental benefits it offers to children.

Playing with playdough provides sensory stimulation and is a very calming experience.

It also provides proprioceptive input.

Proprioception is a sense of where your body is in space, which children require in order to develop skills such as balance, movement and how much muscle force to use.

When children use their hands, fingers, and tools to pound, push, poke, shape, roll and cut the playdough, they are developing the small muscles in their fingers and hands.

Through these manipulations, children also develop their hand-eye coordination.

These are both critical areas of physical development for writing, drawing, playing, eating and many other purposes.

Using playdough supports children’s capacity to be creative and develop their imagination skills.

Creativity is a very important life skill that helps children develop strategies to overcome problems and find solutions.

Playdough offers open-ended play, which stimulates curiosity, another important life skill and character strength.

Creating with playdough supports children to feel competent and proud of their accomplishments.

It is a great outlet for children to express their emotions.

Playing with playdough in small groups and/or with adults presents lots of possibilities for talk and discussion, playing collaboratively, problem solving and planning with others.

Through playdough, children build their vocabulary and practice listening to and talking with friends, siblings, and adults.

When making a batch of playdough, children start to understand the purpose of written language. Following the recipe instructions helps children to connect written and spoken words, to learn that writing can be used for different purposes.

When children play with playdough, they are measuring, counting, sorting, classifying and learning about shapes, weight and volume.

Playdough is also an excellent tool for teaching the alphabet, by having children form letter shapes with the playdough or experiment with alphabet cutters.

Ingredients:

1 cup of flour (any kind)

1/4 cup of salt

1 Tablespoon cream of tartar (optional)

1/2 cup warm water

1/4 teaspoon non toxic food colouring powder

(Note: if you don’t have colouring powder, you can also use a drop of non-toxic gel or liquid colouring. Just make sure you mix it thoroughly!)

Knowledge is life – we know you’re never too old or too young to start learning. At Explore & Develop Parramatta, our Educators are intentional in their teaching and educational programs, while following children as authors of their own learning. Together, we inspire each other and ensure we are open to learning for all.

We are lifelong learners, supporting children to have the best start to schooling with our ‘transition to school’ and ‘foundation for life’.

We are a ‘home away from home’. Partnerships between families and Early Childhood Education and Care Services are like a puzzle – we work together, we share our knowledge – coming together for your child.

We co-ordinate additional external services to connect with our community, working with Parramatta Council, dentists, speech pathologists, health care professionals and learning providers for a variety of

in-house opportunities to support children’s learning and development. Our Service also has a local artist who inspires our children weekly through art and cultural knowledge.

Our learning spaces speak for themselves, designed for open-ended exploration, holistic learning and opportunities for endless discoveries.

We source high quality and sustainable resources, supporting local businesses and communities. The children have many opportunities to run, explore and express themselves in our outdoor environment.

Your child will be excited to come to Explore & Develop Parramatta, where a day of learning through play awaits. Through play, we ignite the children’s curiosity, imagination, creativity and their learning. Risky play, dramatic play, sensory play, exploratory play, schematic play, creative play, symbolic play, and much more. The opportunities for play are endless!

After so many years of caring for and educating children, families always return, referring more families and their friends. Explore & Develop Parramatta is not just a service, it’s a family. We have been individually owned operated since opening our doors 16 years ago for my daughter, Isabelle. Sixteen years on, both my daughters are working alongside me as passionate, dedicated Educators who strive for quality and excellence.

We are sure you will agree we are the right fit for you!

Please feel free to call us on tel: (02) 9898 1100 or enquire here. We’d love to hear from you!

An interest in immersing ourselves in an imaginary magical world was sparked early last year as the children were exploring sounds and listening to instrumental compositions. One particular soundscape that featured twinkling chimes and suspenseful highs and lows became the ‘fairy music’ and was a prompt to drive imaginary dramatic play.

Without any physical resources, the children as a group created their own fantastical imaginary world. We explored dark swamps in rickety boats, avoiding crocodiles and keeping an ear out for those dangerous wolves and yetis. Luckily, our world was also inhabited by fairies who often helped us get out of sticky situations by gifting or using their magic.

As the world expanded and more children joined in the fun, the play naturally developed some unspoken rules, roles and a predictive narrative. While boys and girls were equally interested and actively participating, I noticed that the roles were seemingly gendered. Some children took a more passive role alongside myself, however, the ‘fairies’ were only played by girls, and the ‘wolves’ only played by boys. I wanted to challenge this idea as I feared this too would become an unspoken ‘rule’ of the game.

As expected, one afternoon for the first time in this play, I heard: “Boys can’t be fairies, they have to be wolves.” Before I could interject, a strong voice made herself heard, and challenged this thought: “Boys can be fairies, there are boy and girl fairies.” Nothing more was said and the play continued, but from this point on, the topic seemed to pop up time and time again.

“Children should not be limited by having to choose to be ‘masculine’ and therefore, ‘not feminine’ and vice versa…. If Educators can learn how gender binaries are ‘maintained and policed’ in classroom life, they have an entry point to disrupting the maintenance of the binary, thus freeing children to ‘be’ rather than to ‘be gendered’.

MAC NAUGHTON, 2005, p87

Children developing their own understanding of gender and identity are doing so through the messages they receive from the world and people around them. In an early childhood setting, Educators can play a big part in challenging and crossing the traditional gender boundaries. Older peers also have persuasive power to disrupt perceived notions of gender.

Throughout the year, the play evolved and branched into different avenues of exploration to support the original, imaginary play. Suddenly, we were receiving letters via our ‘fairy tree’, making potions in the art studio to aid our adventures, and decoding information using our fairy encyclopaedia. In these settings, I noticed a few boys who had a strong interest in the play, resist and reject it when the fairies took centre stage, because of their gender.

While I wanted to challenge this and help them feel comfortable and confident, I also recognised that many of our older children were already challenging these ideas verbally between themselves. It seemed to have a great impact on the children, especially in spaces like the art studio, where they often made potions and discussed their theories about fairies and magic. It helped to have resources that were inclusive of boy and girl fairies, like the fairy encyclopaedia that showed off illustrations of boy fairies riding fish and hiding in cacti, and the introduction of a small male fairy into the potion making space. Slowly I observed those same boys becoming very involved with fairy business, even hearing a few of them say, “I wanna be a fairy”.

The Anti-bias Approach encourages Educators to consider the implications of gender in relation to social and political power and be conscious of the impact our pedagogical choices can have on children’s developing identity.

“There are many competing discourses, or ways of knowing ourselves and the world, and these produce a range of effects. Translated into the everyday politics of classroom life, this means some ways of being a boy or a girl are more possible, desirable and powerful than others” (Smith, Campbell and Alexander, 2020, p61).

The imaginary space can and should be a safe place for children to explore their own role in a group, as an individual, and express new ideas, including those about gender. In our fantastical world where wolves can be frozen with magic apples, and yetis can swing between aeroplanes, why can’t boys be fairies?

References

Mac Naughton, G. (2005). Doing Foucault in Early Childhood Studies; Applying Poststructuralist Ideas. Routledge: New York, United States of America

Smith, K., Campbell, S. & Alexander, K. In Scarlet, R. (ed), (2020) The Anti-bias Approach in Early Childhood (4th Edition). Multiverse Publishing: Sydney, Australia.

It is fantastic to see 80 per cent of the population of NSW being double-vaccinated. This is a great step in protecting vulnerable people in our communities and a big help in getting life back to normal.

Of course, during the pandemic, the Early Childhood Education and Care sector became an essential service and our teams adapted to the challenges of working on the front line.

I am really proud of the efforts of everyone in the Explore & Develop community – educators, children, parents, and of course our franchise owner/operators over the last few months for doing everything possible to maintain a safe environment for all.

In this newsletter I would like to share the latest research on the impacts of COVID-19 on young children and what role families can play to help keep them safe.

I am also happy to share some positive changes that have been made to the Child Care Subsidy that will provide greater financial support for some families.

I am looking forward to a brighter 2022 where we can enjoy all the freedoms whilst staying safe.

Kind regards.

Belinda Ludlow

CEO of Explore & Develop

It is mandatory for all Early Childhood Educators and staff across NSW to have received two doses of COVID-19 vaccination by Monday 8 November 2021 and all Explore & Develop services will be compliant with this requirement.

Explore & Develop services follow the current requirements and advice of NSW Health and take all necessary precautions to minimise the risk of further transmission of COVID-19 in our service community.

In addition to vaccinations, our Explore & Develop services have implemented a number of control measures that have included increased cleaning and hygiene practices and altering requirements to drop-off and pick-up procedures to suit each specific location.

Recent data published by the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NIRS), with the support of the NSW Ministry of Health and NSW Department of Education looked at the transmission of COVID-19 in schools, early childhood settings and households in 2020 and 2021.

The research concluded that although most children in this study had no or mild symptoms from COVID-19, however, household transmission was a much more pressing issue.

The report findings indicated that the impact of cross contamination of COVID-19 for children that attended an Early Childhood Education and Care service or school, was the highest in the family home. In their studies with this age group, they found 70.7 per cent of overall transmission was among household contacts.

Additionally, the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute recommends that to protect children and adolescents in the community and keep schools and Early Childhood Education and Care services open, we should encourage parents and adults of all ages to be vaccinated now.

We are confident that this, in combination with support from our community, will minimise risk and help to keep the Explore & Develop services open and children learning face-to-face beside their peers. This is so important, as we know that children’s brains develop connections faster in the first five years than at any other time in their lives.

A child’s participation in an organised Early Childhood Education program assists in the development of their cognitive abilities and also enhances their social and emotional skills while they interact with their peers.

In fact, “full participation in education is essential for children to learn and develop socially, but also for family and societal functioning,” says Doctor Archana Koirala, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Specialist at the University of Sydney.

Ultimately our priority is to minimise risk as much as possible, so that all children and families can experience the benefits of Early Childhood Education and Care.

Under the current Child Care Subsidy arrangements, the Federal Government capped the maximum benefit that it contributed to the cost of child care at $10,665 per year for families that earned over $190,015. However, from Friday 10 December 2021, this annual cap will be removed, meaning that more families will be able to benefit from this increase in funding.

This is an important change, as many families would cease receiving Child Care Subsidy half way through the year and were required to cover 100 per cent of the cost of care for the second half of the year. As a result, some families were forced to limit the amount of days that their child or children attended, by either seeking care by other means, or limiting the number of days of workforce participation.

In addition, from Monday 7 March 2022, families with more than one child may be eligible to receive a 30 per cent higher subsidy, up to a maximum of 95 per cent subsidy for the second and younger siblings. This increased subsidy is available for families earning less than $354,305 per year, who have more than one child aged five or under, who attend Early Childhood Education and Care.

If you would like to estimate how the increased Child Care Subsidy will affect your child care fees (as of Friday 10 December, 2021) please utilise the Explore & Develop Child Care Subsidy Calculator.

We are encouraged that these changes to Child Care Subsidy will be implemented, assisting to make Early Childhood Education and Care more affordable and accessible to families.

Sustainability is a key facet of our curriculum. Embedding sustainable practices, communicating environmental responsibility, and observing environmental stewardship and activism in our children are regular, deep, and underlying parts of what we do. In line with the service philosophy, embedded sustainability practices exist across the service that encourage environmental responsibility. Sustainability motivates all decision-making, from management to curriculum. But what more could we be doing?

Late in 2020, we engaged in critical reflection around sustainability. Educator action research projects ignited a sustainability review which identified a missed opportunity in meal processes. Recognising the excess waste that was created through sourcing all meals through an external caterer, we saw an opportunity. We transitioned to preparing and providing our own afternoon teas. This change allowed for utilising leftovers (in line with Food Safety guidelines), executing resourcefulness and repurposing excess foods for cooking experiences. In addition, the change also encouraged the facilitating of: regular, relevant classroom cooking experiences; opportunities to eat produce from our garden; and meaningful connections in garden-to-plate-to-garden learning.

“Education for Sustainability (EfS) is about transformative change at many levels- our thinking, our ways of being and our ways of acting to regenerate the Earth. Many educators readily engage in the tangible aspects of EfS in early childhood services, such as establishing compost bins, recycling and growing produce. But, there are deeper layers of meanings about thinking and being that can be explored with children through our daily practices.”

(Dr. Sue Elliott, 2019)

A routine is something that is repetitive. Rituals are those ‘special’ actions that add magic and emotion; that deepen the connection and relationship (Loader & Christie, 2017).

Afternoon tea has become a cultural practice, a ritual developed over time. The reciprocal action of ‘feeding the school’ has fuelled the sense of community as children have embraced the practice. A layer of pedagogical magic has developed around what once was just a routine task. The children have been empowered with agency.

Cooking has also become a place for educators to share their home cultures with our little school on the roof, adding delicious recipes that reflect the multi-cultural make up of our community. Dia has shared her childhood favourite, coconut soup. Linnie has taught us all how to make Vietnamese rolls. Sandra’s red bean pastries are a firm favourite.

The menu is prepared every week with each class planning for their day. The Outdoor Teacher coordinates the plan and identifies key ingredients for inclusion. Excess foods are saved from becoming waste, instead resourcefully planned to use in the upcoming menu. For example, last week, a corn salsa served at lunch was transformed into a corn dip served with school-grown, and much anticipated, snow peas. The week before, leftover tortillas were coupled with warrigal greens from the garden to become quesadillas, cooked fresh at the table. Early weeks saw on average two baked dishes, with easily prepared foods served on the other days. As educators and children have settled into the practice, it has shifted from a ‘job to do’; they are now excited to cook, and subsequently more complex dishes are increasingly on the menu.

Most recently we have seen dishes directly reflecting the children’s curriculum and interest. Our Bilby children have begun working with tools, creating resources for their sound project. To extend on this, we trust our toddlers with knives as they cut vegetables to be served with dip. Food was melded with storytelling when the Wombat children wanted to create a “Pirate Pie” for the school. With imaginations on, the Wombats told their educators they needed the filling to be coral-slime. This delicious sounding concoction was achieved with warrigal greens from the garden, cooked with mushrooms. Yum!

The changes have totalled to be much more than the sum of the parts. What began as a sustainable action, primarily driven by a desire to reduce food waste, has become something much more. An act of care, an opportunity to share love, culture, and deeper-rooted connection to the land; growing, sharing and eating together.

Elliott, S. (2019). Education for sustainability. The Spoke. [Blog]. Early Childhood Australia. 1st, May, 2019.

Loader, M. & Christie, T. (2017). Rituals: Making the everyday extraordinary in early childhood. New Zealand: Child Space.

At Explore & Develop Annandale, we embrace the transformative practice of looping—where teachers build deep, lasting bonds by staying with the same group of children for at least two years. Rooted in the Steiner philosophy and backed by decades of successful experience, looping goes beyond mere continuity of care. It fosters meaningful, ongoing relationships that create a warm, nurturing environment where children can truly thrive.

While much of the literature highlights the benefits for children, such as secure attachments, stronger peer relationships, and smoother transitions (ACECQA, 2023. Colwell, et al, 2017. Degotardi, et al, 2025. O’Connor, 2022. Our Place, 2021) less attention is given to the professional impact on teachers. At Explore & Develop Annandale, we have been practising looping for the past 6-7 years, with educators and teachers engaging in looping cycles that sometimes last for three or even four years. This provides a valuable opportunity to reflect on how this approach shapes both teaching practice and professional identity. The following reflections from educators Sandra, Linh, Jen, and centre director Su, demonstrate how looping influences relationships, pedagogy, and the professional lives of teachers.

For Sandra, looping has reinforced the importance of trust and emotional connection in her teaching identity. She describes herself as a “slow warmer,” someone who takes time to build relationships. Looping has enabled her to do just that, strengthening her bonds with children and families over time.

“When I see the same group of children again, even after a gap, our relationship comes back quickly. That sense of belonging makes settling easier for everyone children, parents, and myself.”

This deep understanding of children enables Sandra to refine her pedagogy, particularly in areas such as transitions and routines. Morning settling, for example, becomes smoother when the teacher understands each child’s temperament, needs, and family background. Continuity enables her to establish consistent expectations over time, fostering a calm and predictable environment for children, families, and herself.

For Linh, looping has been nothing short of transformative, what she describes as “another degree” in her professional journey. Staying with the same group of children and families has provided her with opportunities to learn about children within the context of their home lives, parenting styles, and attachments. She refers to this as the “contextual foundation” of her pedagogy.

“I’ve shifted from being a Steiner-inspired teacher to becoming more of a project builder. I trust children more, and I believe more strongly in their citizenship.”

With the same group of children over time, she has been able to ask more profound pedagogical questions: Could this project be more engaging? How can excursions be organised differently? What new learning experiences could emerge from children’s evolving interests?

Linh also acknowledges the challenges: self-doubt, losing team members, and the patience required to rebuild relationships with new families. Looping can also create bias, as familiarity may obscure new insights into children until another educator offers a fresh perspective. For her, these challenges have reinforced the importance of teamwork and firm philosophical grounding what sustains her practice is the shared commitment to children’s rights and social justice.

Jen describes looping as “an enjoyable and rewarding process,” enabling her to watch children grow from toddlers to confident, school-ready learners. With time, the trust developed with families creates a partnership that makes decision-making more straightforward and collaborative.

“By the time children are five, families and I have already shared years of trust. That makes conversations about children’s wellbeing so much easier.”

One of the most significant benefits she notes is how looping smooths the transition to the start of each year. Knowing children’s routines, friendships, and strengths allows teachers to begin planning meaningful learning immediately, rather than spending the early weeks focused solely on relationship-building.

Jen also recognises the complexities such as when children from a previous year still seek her support while she is establishing bonds with a new group. Yet looping, she argues, reduces this challenge by aligning transitions more naturally with children’s school entry. She also reflects on the potential concern that some families may not connect with their looping teacher; however, she stresses the role of the teaching team in ensuring children benefit from diverse perspectives and approaches.

Centre director Su values looping for the strong relationships it fosters between educators, children, and families. Yet she also recognises the unique pressures it creates.

For preschool teachers, the end of the year can feel like being “in two places at once”: saying goodbye to children moving on to school while simultaneously welcoming a new group and their families. Teachers and educators transitioning to younger groups require time to establish connections with a new group of children and their families.

Su suggests that these challenges can be mitigated by collaborative structures, teaching partners, and the broader team sharing responsibilities, and leadership ensuring children stay connected to the centre community even after moving on. Her perspective highlights that looping is not just about relationships with children; it also requires systems of support for educators.

Taken together, these reflections show that looping is not just about children’s security and belonging, but also about teachers’ professional growth and identity.

Looping is more than just a staffing approach it is a relational, pedagogical, and professional commitment. The reflections from Sandra, Linh, Jen, and Su show that when educators can stay with children over time, there is deeper trust, more insightful observation, and more meaningful learning. Current research supports these views, emphasising the importance of continuity in relationships, emotional security, and teacher well-being as the foundations of quality early childhood education.

While looping presents challenges such as balancing continuity with fresh perspectives it offers a profound opportunity for teachers to evolve alongside the children they teach. At Explore & Develop Annandale, the practice has demonstrated that continuity of relationships not only enriches children’s lives but also strengthens educators’ sense of purpose, professionalism, and capacity to lead learning.

ACECQA. (2023). Continuity of learning practices: Information sheet. Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-07/InformationSheet_EYLF-Continuity%20of%20lear_Practices.pdf

Ceglowski, D., & Bacigalupa, C. (2015). Continuity of care in infant/toddler programs: A resource guide. Start Early. https://www.startearly.org/app/uploads/2020/09/PUBLICATION_NPT-Continuity-of-Care-Nov-2015.pdf

Colwell, N., Gamble, J., Cprek, S., & Talmi, A. (2017). Continuity of care and child outcomes: A systematic review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 39, 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.02.002

Degotardi, S., Sweller, N., & Pearson, E. (2025). Teacher-child relationships, early childhood programme quality and toddlers’ early academic abilities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 73, 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2025.05.010

O’Connor, E., Collins, B. A., & Supplee, L. (2022). Three decades of research on individual teacher-child relationships: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 7, 920985. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.920985

Our Place. (2021). Continuity of learning: Supporting positive transitions for children and young people. https://ourplace.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ourplace-continuityoflearning.pdf

For children under five, sharing and turn-taking are foundational social-emotional skills that develop gradually through experience, adult modelling, and guided support. As adults, our role is not to referee play or stifle their decisions, but to enable children and support the choices they make when sharing and taking turns.

Children need to learn to share to build and maintain friendships, play cooperatively, take turns, negotiate, and handle disappointment effectively. Sharing teaches children the importance of compromise and fairness. They understand that if they give a little to others, they can also get some of what they want. However, it is important to remember that children shouldn’t be forced to share something they are actively playing with just because someone asks.

The above occasions help children practise being assertive and explaining why they won’t share. Depending on their language skills, they may communicate this in different ways, and their adults need to support their choices.

At E&D Annandale, if a child is using a resource or if a space does not accommodate more children, a conversation will occur, during which negotiations will take place to determine when the child can use the resource or take a turn. We consistently encourage children to use phrases like “I am using this now, but you can have it when I am finished” and “There isn’t space for you right now, but I can let you know someone is finished”. With younger children, we will use this language for them and encourage a simplified version, like “You play after me”.

We also support children to ask for a turn with phrases like “You can ask Georgia for a turn when she is finished”, or “You have lots of trains, Georgia. Could Jen please have some too?”

There are many times when it is kind for children to share their toys with their friends. Children need opportunities to learn about and practise sharing. At home, you might want to use some of these ways to encourage sharing in everyday life:

Toddlers are learning to share; it’s challenging for them to understand why they must wait for something. Sharing often requires children to manage their emotions, and toddlers are only beginning to learn how to do this. Sometimes, toddlers try to take something from another child because they can’t wait, which can lead to upset feelings for both children. We strive to ensure that there are sufficient resources and play spaces are set up for meaningful play. However, when a disagreement arises, we view it as an opportunity to teach them how to make a request and respond respectfully.

By the age of 3, many children begin to understand the concepts of turn-taking and sharing. This includes concepts of sharing equally and what is considered ‘fair’; however, individuals may still be reluctant to share if it involves giving up something. A good way to help them is by practicing lots of turn-taking.

So, what does turn-taking mean? Turn-taking, or the act of taking turns in a situation, conversation, or even sharing space and time with another individual, can manifest in various ways.

As you can see, taking turns is part of daily life. Although we minimise the time children wait throughout a preschool day, children still need to wait. This could occur while they wait for a snack, to use the bathroom, transition to lunch, wait for a toy, or wait for their turn in a game. As children are exposed to more opportunities to practice taking turns, they develop patience and improve their ability to do so. However, when they first start, taking turns can be frustrating for both children and teachers.

Young children learn new skills every day, and this process is even more accelerated when they are in groups with other children. A child’s environment can include a variety of objects that they would like to use while others are using them.

Taking turns isn’t a skill children are born knowing how to do. In fact, as babies, we are all very self-serving and aware of only individual needs. This developmentally serves the infant and baby. Crying out is a survival instinct. There is no “turn-taking” in sleeping through the night or wanting to be fed at all hours of the day!

Turn-taking develops as a skill through modelling and observation, and then through practice with age.

Several developmental components play a role in turn-taking abilities:

Young children learn how to share through ample opportunities and supported facilitation from adults. When children are in a group with other children, opportunities to learn how to take turns come in a variety of forms, such as waiting for an object, waiting to participate in an activity, and waiting for their turn when they are in a large group completing a similar task.

Below, you will learn some simple ways to support turn-taking activities using visuals.

Visual Supports- Visuals support children in understanding what another person wants. Visuals can be utilised in parent-child relationships, teacher-child relationships, and even child–child relationships.

As children learn more words, they become able to comprehend directions (both new and familiar). However, before they understand the meanings of words, visuals can help communicate a message.

Other visual supports can include:

Verbal supports – As an early childhood educator, I like to give children the opportunity to play with an object for as long as they want, without imposing a time limit. I don’t use timers in my class to indicate when a child needs to finish with a toy.

When children play with toys, they use them for a purpose, and it can be frustrating to hear a timer go off in the middle of their game. This can cause frustration in the child due to having to end their play, and some friction with the child who will be receiving the toy.

Instead, we say the phrase “when you are all done, then _________ would like to play.” Typically, when a child is finished using a toy within a reasonable timeframe, the waiting child gladly accepts it.

Verbal supports can include:

https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/behaviour/friends-siblings/sharing

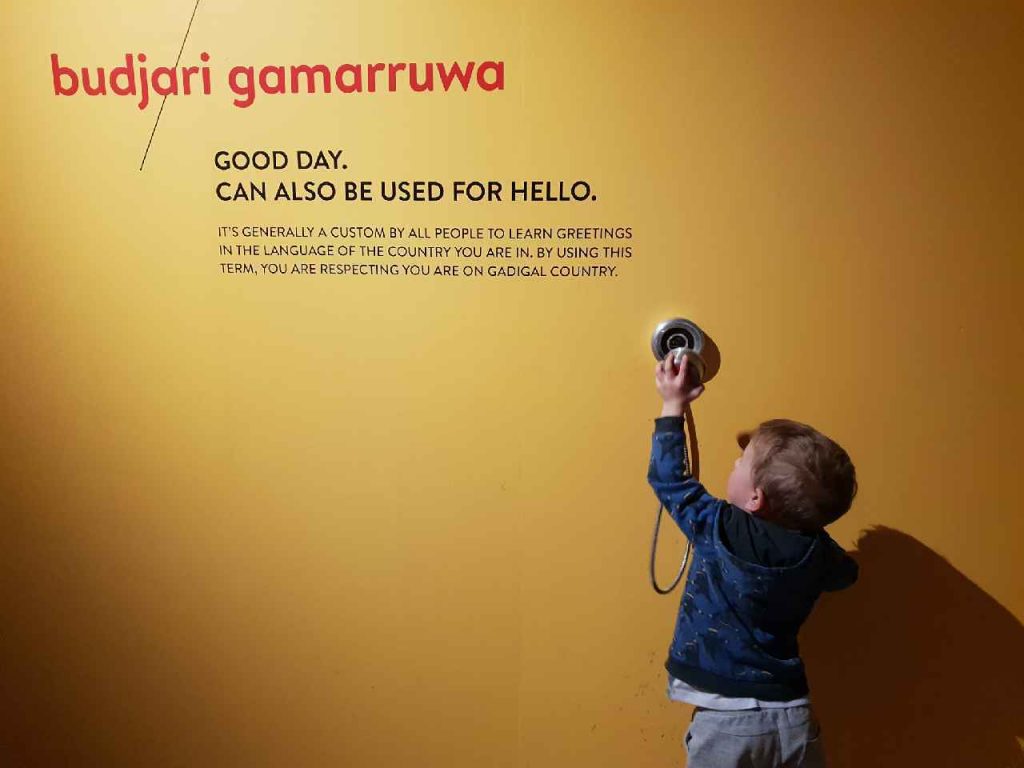

The educators, children and families at Explore & Develop Annandale acknowledge the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation as the traditional Custodians of the Country upon which we learn and play.

We acknowledge First Peoples’ ongoing connections to Lands, Seas and Community. We pay our respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. We extend our respects to our Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander colleagues.

At the 2020 Inspire conference in Naarm (Melbourne), Gheran Yarraman Steel, a proud descendant of the Boon Wurrung People of the Kulin Nation, welcomed us. In his welcome, Gheran shared with us that the path to reconciliation begins with knowing the history of place. Gheran encouraged us to ‘come [with] purpose’ and to think about our ‘responsibility of knowledge’. This resonated with me.

As teachers and educators, it is our role to listen with open hearts and minds and to responsibly share what we learn with families, children, and the wider community—to do our best until we know better.

We recently wrote and published an Acknowledgement of Country book, which exemplifies our listening and our responsibility to acknowledge the history of our place and share the knowledge we have built thus far. The book includes many of our educators’ voices. The words in between have been written by Madeleine Gill, a Jerrinjah women and teacher, with Su Garrett and Melanie Elderton.

An Acknowledgement of Country is a way of showing respect for the Traditional Custodians of the Country you are on and can be given by both non-Indigenous people and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples who are connected to another place (Staines & Scarlet, 2018).

This is different to a Welcome to Country, which is a formal welcome onto Land and can only be delivered by the Traditional Custodians of that Country or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples who have been permitted Traditional Custodians to welcome visitors to their Country (Martin, 2016).

First Nations’ Peoples are intrinsically connected to Country;

“…they speak to Country, sing to Country, visit Country, worry about Country, feel sorry for country, and long for Country. People say that country knows, hears, smells, takes notice, takes care, is sorry or happy…” (Rose, 1996. p.7).

You will often see Country, Lands, and Seas capitalised in the context of Indigenous culture because Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples discuss and refer to Country as they would a person. In this context, these words are considered proper nouns, not just descriptors (Rose, 1996). For Aboriginal people, Country is a living being that they care for and cares for them in return.

Connection to Country is important, whether a person lives in the city or in a rural area. From the time of the Dreaming, this spiritual connection and care for the Land has been integral to the very being of First Nations Peoples (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies [AIATSIS], 2011).

Here is the land, here is the sky

Here are my friends, and here am I

We acknowledge the Gadigal people

The traditional custodians of the land on which we learn and play

Hands up, hands down

We’re on Gadigal ground

Budjari Gamarruwa (Gadigal greeting)

We raise our hands to the sky that covers the Gadigal Land

We place our hands on the ground in the care of the Gadigal Land

We place our hands on our hearts in the love of the Gadigal Land

Petuwa (Gadigal – to share warmth or love)

In 2016, we reflected on the first 3 years of our operation and planned for our future. One outcome was the agreement that we didn’t know enough about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. We had resources; we had undergone a small number of whole team professional development sessions. However, they didn’t have the impact needed. If we didn’t know, what could we share with our communities?

We made learning our priority and connected with Jess Staines at Koori Curriculum. We committed to the professional development of the entire team over a period of several years. This experience gave us the confidence to give things a go and connect with the community, both within and outside of the early childhood community.

Once we connected with Jess we assessed how well our philosophy connected with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. Our first step was implementing a daily Ritual of Acknowledging Country. Jess introduced us to the Acknowledgement written by Auntry Tracey Linn Bostock a proud Bunjalung/Mulungjali woman who was born in Brisbane, QLD and moved to Sydney in 1962 and is now residing along the inner west Goola’yari (Cooks River) Tempe with her family.

The original words and actions that Aunty Tracey created are to educate and guide children to understand the importance of knowing the traditional land that they live and play on and how to care for and respect the land is as follows:

“I would like to Acknowledge the (name of clan/tribe of country) and other clans on whose land we are now gathered on.

I acknowledge the spirits of the land, our Elders past, present and future and especially the children of the land.

I pay my respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that are here with us also.”

“We touch the ground of the (name of clan/tribe of country) land

We reach for the sky that covers the (name of clan/tribe of country) land

And we touch our hearts for the care of the (name of clan/tribe of country) land”

Aunty Tracey’s songline has been shared (with permission) within Inner West Council Children and Family Services, her communities, statewide, nationally and internationally. It also made its way onto ABC’s Play School song “Hand in Hand” for the Acknowledgement of Country episode in July 2019. (Scarlet & Bostock, 2022).

Aunty Tracey Linn Bostock has always asked that when the Acknowledgement of Country for children is shared that you know the history of who created the Acknowledgement and the reason is, when it comes to Black History in the past some words and names are changed or deleted and claimed by others. Aunty Tracey has always wanted to share her songline with community and be recognized and acknowledged for her Aboriginal culture in early childhood education.

References

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, [AIATSIS]. (2011). The Benefits Associated with Caring for Country:

Literature review. https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/research_pub/benefits-cfc_0_3.pdf

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, [AIATSIS]. (2022). Welcome to Country. https://aiatsis.gov.au/

Boomali. (2024). Tracey L. Bostock. https://boomalli.com.au/artist/tracey-l-bostock/

Goodwin, J. & Hydon, C. (Eds.). (2023). Reconciliation in Action. Early Childhood Australia Inc.

Martin, K. L. (Ed.). (2016). Voices & Visions: Aboriginal early childhood education in Australia. Pademelon Press.

Narragunnawali. (2024). Acknowledgment of Country. https://www.narragunnawali.org.au/

Rose, D. B. (1996). Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal views of landscape and wilderness. Australian Heritage Commission.

Scarlet, R. R. (2016). The Anti-Bias Approach in Early Childhood (3ʳᵈ ed.). Multiverse Publishing.

Scarlet, R. R., & Bostock, T. L. (2022). Acknowledgement of Country: The original story. The Inclusion Room.

Staines, J., & Scarlet, R. R. (Eds.). (2018). The Aboriginal Early Childhood Practice Guide. Multiverse Publishing.

Yunkaporta, T. (2019). Sand talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world. Text Publishing. https://cat2.lib.unimelb.edu.au:443/record=b7338253~S30

Our overarching goal is to improve children’s lives by providing them with the tools needed to succeed in life. To do that, we need a committed team of pedagogically aligned teachers and educators.

Educators are the heart of early education; we understand that creating and maintaining a positive workplace culture is critical to maintaining educator engagement and retention, which is beneficial for the continuous relationships between educators, families, and children. Research shows educators feel more engaged when their voices are heard, and action occurs. Therefore, in our Service, we have developed systems for educators’ voices to be heard and valued.

Our team created service values very early in our inception; these values became our philosophy. Trust, Play, Belonging, Inclusion, Knowledge, and Wonder, have framed our pedagogical direction and critical reflection. In all decision-making, we ask ourselves, will this fit our values?

Team cohesion is vital for a positive workplace. It is built through communication and educators understanding themselves, each other and their roles. To develop an understanding of themselves and others, all educators have participated in personal DISC assessments. “The DISC Advanced assessment is a valuable tool that can be utilised for self-awareness and the personal development of the respondents, in conjunction with a properly facilitated process” (DISC Assessment workbook). These assessments are valuable for individuals to understand how they behave and react to stress and pressure and their preferred way of communicating with others. When debriefing as a team, educators can understand each other better, primarily in how we communicate, resulting in a more cohesive team. These reports are now integrated into our Personal Development Time meetings (Appraisals). They provide insight into each other’s communication styles and preferences and inform reflective questions, as a continuous cycle of reflection by team members, and support developing relationships in new teams.

We recognise the significance of whole team development alongside individual professional growth. To facilitate the entire team’s professional development, we have engaged in professional development projects with specialised consultants over extended periods, ensuring we have time for deep learning and critical reflection on a particular topic. For example, we have been connecting with Koori Curriculum since 2016, learning how to deeply work through embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in our program.

Educators’ connection to change is another way to enable a positive workplace culture. Several years ago, we embarked on a project to change the way we organised groups of children to create smaller groups and develop educator engagement . Over a six-month project, educators researched grouping possibilities, decided how the grouping structure would work, considered the impact on the learning environments and initiated a new daily flow.

Through this change we coined the term ‘Things belong to places, people belong to each other.’ to describe our new way of working. This change enabled a more collaborative and transformational leadership structure best supporting children and enabling the professional growth of our teachers.

A practice we have created to enable critical reflection is through thinking pairs. We use thinking pairs when undertaking professional development webinars to provoke critical reflection of practice or to critically reflect on documents like the new EYLF 2.0 or our service philosophy. Essentially, it is a pair of educators who critically reflect together. Our educational leader intentionally constructs thinking pairs to critically reflect on a practice. They are curated to ensure educators are paired with others with different years of experience, different levels of qualifications, different lengths of time working at the service and working with different groups of children. Constructing pairs this way provides space for multiple perspectives and the opportunity for informal mentor/mentee relationships to develop. Working in pairs provides space for quieter voices to contribute to professional dialogue. It also honors the opinions and ideas of all educators, regardless of their qualifications, experience or position.

The most important thing we have learned about engaging our team is to listen. We meet each educator where they are and continually reflect on their needs to build their sense of belonging to our team.

Is your child about to start early education and care?

For parents and caregivers the most daunting adjustment can be the anxiety of being apart for the first time or worrying about how your child will cope through this change. Separation anxiety is common, although easily addressed with a positive outlook and a few expert tips from professional educators.

This change can be as challenging for the child as the grown-ups involved. You may find that you both have an unexpected emotional response. For this reason, it’s important to focus on the benefits so that all parties can quickly transition into a healthy, happy routine.

Most early childhood services will have an orientation prior to commencing, which may be a couple of hours in care for you and your child to familiarise yourselves with the new surroundings and routine.

You and your child will likely have some mixed emotions on their first day of care. Expect that you will both be excited and nervous about this new experience. Your child will look to you for what to do/how to respond.

Every child and family is unique, so communication is the most effective way to navigate this milestone. This experience is new, but it can also be exciting, and should be nurtured with the positive attention that it deserves.

Talk honestly with each other at home, and draw on the support of the educators, who are highly experienced with the challenges of families and children encountering new routines.

As you work together with your early childhood service, you will feel informed and empowered by the experience, so that you can be the best support to your child as they grow and adjust.

“When we feel safe, we explore, we learn, we grow”.

— (Kids Matter, Australian Early Childhood Mental Health Initiative)

More than 44 per cent of NSW children are not developmentally on track when they start school, according to the latest Australian Early Development Census, an Australian government initiative that measures how children have developed by the time they start school.

The census looks at five key areas of early childhood development: physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills, and communication skills and general knowledge.

Language and cognitive skills saw the most significant shift in the most recent report, with the percentage of children who were ‘developmentally vulnerable’ in this area increasing from 6.6 per cent in 2018 to 7.3 per cent in 2021.

Not being developmentally on track can have significant and lifelong consequences for a child.

The early years of a child’s life are critical for their cognitive, social, and emotional development. This period is marked by rapid brain development, where the foundations for future learning, health and wellbeing are established.

Research has shown that participation in high-quality early education and care leads to better outcomes at school and later in life.

“The first five years of a child’s life are vital for their health, development, learning and wellbeing. Children who participate in quality early childhood education and care, and who get the right support services, such as health and development checks, are more likely to succeed at school and have improved lifelong educational, social and economic outcomes.”

Reference: ‘Putting a Value on Early Childhood Education and Care in Australia’

In the report ‘Work and Play: Understanding how Australian Families Experience Early Childhood Education and Care‘, 83% of parents said that educators and carers have a significant impact on young children’s learning and wellbeing.

“Parents clearly see the early childhood education and care sector’s value in providing an environment of support and growth and setting children up for success at school and beyond, with this belief strengthening as their children approach school age,” states the report.

The two most popular options for preschool are Community Preschool, or a preschool program within an Early Childhood Education & Care (ECEC) service. ECEC services are often referred to as daycare/childcare centres but these are outdated terms that can cause confusion about what the services actually offer.

Opening hours

Hours of school preparation

Convenience

Parents identify that the benefits of early childhood education and care accrues beyond the child to the whole family, and extend beyond the monetary benefit of income earned while young children are in education and care.

According to the report, ‘Counting the Cost to Families: Accessing Childcare Affordability in Australia; The Front Project’.: “77 per cent of parents surveyed agreed that access to early childhood education and care services is important for the mental health and wellbeing of the whole family.”

One of the benefits of choosing an Explore & Develop service is that they are independently owned and operated, with the owner onsite to oversee daily operations.

While every Explore & Develop service is tailored to the needs of its local community, they have the following important features in common:

Find an Explore & Develop service near you.

Childcare, daycare, early learning, preschool… however you refer to it, it is one of the most important decisions a family will make during the early years of their child’s life.

Due to its fundamental role in a child’s development, the early education and care sector has moved far beyond merely “childcare.”

Research by the NSW Government shows that 90 per cent of brain development occurs in the first five years of life. As the brain grows, it is strongly influenced by what is happening in a child’s environment and their interactions with people around them.

Enrolling your child in early education is a valuable opportunity to help them explore their world and develop new skills that will stay with them as they grow.

We know that choosing where to send your child can feel overwhelming. We support new families through the process every day, so have identified some important considerations to help guide you in making the right decision for you and your child.

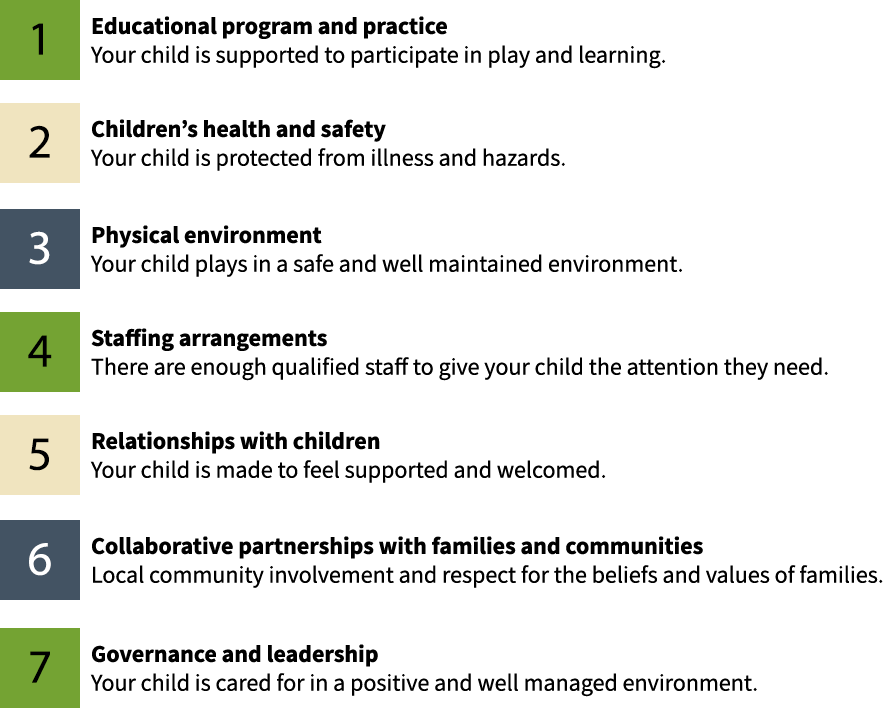

There are several different options for early learning and care, all of which are covered by a national regulatory system known as the National Quality Framework.

The options include:

Early education and care services

This type of service is often referred to as daycare/ childcare centre/ long daycare.

However, these are all outdated terms that can cause confusion about what the services actually offer.

Led by university qualified early childhood teachers, these services provide early education programs, including preschool (transition to school) programs, along with offering extended hours to better accommodate the needs of working families.

These services operate during school holidays, and usually accommodate children from around 6 weeks to 6 years of age.

One of the benefits of attending early education and care services is consistency for children and families, as a child can begin in the infant or toddler group and then move through to the preschool age group, having developed a sense of belonging within the service and trusting, respectful relationships with their educators.

Community preschools/kindergartens

Community preschools offer education and care during school terms and school hours only, which may be more difficult for working families to manage. Generally, due to the more structured nature of preschool programs, families will have less flexibility and choice regarding which days their child can attend the service.

These services usually only accommodate children from 3-6 years of age.

Family daycare services

Family daycares offer small group care in a qualified early childhood professional’s own home.

These services tend to be more focused on providing family-style care and may offer children less opportunity for social development due to the small number of children at each service.

All service types in Australia are regulated under the National Quality Framework and are monitored and assessed to ensure legal and quality requirements are met.

Ask the services that you’re considering what their ratings are in the seven National Quality Standard areas, as listed below:

To ensure your choice of care is a successful one for your family, it is important to make sure it will be convenient for you on an ongoing basis.

Things to consider:

The National Quality Framework also sets out the minimum educator to child ratio requirements, and minimum qualifications of educators, for all early education and care services.

As part of these regulations, all services are required to have a minimum number of university qualified early childhood teachers, depending on how many children are being educated and cared for at the service.

Things to consider:

Does the service director have the maturity and experience to enact decisions on their own and support you when you need it?

Is the service director an owner or an employee?

One of the benefits of choosing an Explore & Develop service is that they are independently owned and operated. The owner is onsite and able to oversee daily operations.

Our highly committed owners are constantly seeking to innovate their services to meet the needs of families and staff, and you have a direct point of contact if you have any concerns.

Not just anyone can become an owner of an Explore & Develop service. We look for early childhood professionals who are genuine in their desire to make a positive contribution to their local community by providing the highest quality early education and care services to children and families.

The next step is to make an enquiry and book a tour with the service. You may need to visit a few on your list to get a feel for the similarities, differences and aspects that you like the most.

Importantly, trust your instincts. You know your child best, and how they might respond to certain environments and people.

Make sure you meet the qualified educators on your tour, especially the ones that will be looking after your child.

On your visit, there are specific things you can look for and questions you may ask. These include:

Establishing quality interactions between children, educators and families is crucial to achieving positive learning outcomes for children. As you walk around the service, observe how educators interact with children and one another.

Look around the space and ensure it is adequately resourced for each age group. Children engaging in a range of play experiences is a positive sign.

Look for play spaces that are age appropriate and provide challenges for children to learn, play and develop.

Outdoor environments should extend and challenge not only children’s physical wellbeing, but also encourage children to take considered risks in their play, all the while developing their problem-solving abilities and building their resilience.

Even though it is a group educational setting, educators should be planning for children’s learning on an individual basis through play-based experiences.

Literacy, mathematical and scientific concepts should be embedded into everyday programs. For example – educators singing, talking and reading with infants and toddlers as well as preschool children is crucial.

Children should be provided with hands-on learning opportunities, resources and materials to promote their development.

The Australian Government supports families in their choice to use childcare while they are at work by subsiding some or all their childcare fees. This is a means-tested system with more financial support for lower income families.

To be eligible for the childcare subsidy, families must provide the age of the child, the child’s immunisation status and the parents’ residency status. In addition, the chosen childcare service must be an approved provider.

Approved providers include centre-based care, family day care, outside school hours care and in-home care. It does not include community preschool/kindergarten.

Our child care subsidy calculator can give you an idea of how much subsidy you may be eligible for.

At Explore & Develop, we will guide you every step of the way and lead you into a partnership where you are a valuable contributor to your child’s learning.

We offer daily programs that reflect a calm, relaxed and unrushed environment for growing and learning. We value the commitment, dedication, and professionalism of our educators and their desire to give every child a great start in life.

All Explore & Develop services are individually owned and operated by passionate professionals who are on site daily, ensuring high-quality education and care.

We have services across NSW. Click on ‘Locations’ at the top of the screen to find the Explore & Develop service closest to you.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to stay up to date with our latest news and resources.

By Linh Dao

The learning of Auslan sign language inspires and enriches our learning journey.

We know that babies and toddlers rely on gestures to communicate with others and by the age of two, their non-verbal vocabulary is significant. Embedding sign language as an intentional teaching practice embraces this very nature in young children’s ways of learning and opens a platform in which adults and children share their imagination and perception of the world.

Dr Elizabeth Austin from Macquarie University, who is well-known for her body of research on the link between gestures and education, states that

“Gestures can reflect real-world objects and communicate some aspects of thought more effectively than words.”

(Austin & Sweller, 2017, p2)

This belief also pays reference to Gardener’s multiple intelligence theory which addresses that we all have different learning styles. As such, when we combine gestures and words to describe something, children who are visual or kinaesthetic learners can connect the verbal explanation to the visual presentation. This dual coding process is believed to improve children’s comprehension and retention.

An example of this learning is when I introduced Auslan signing for Isabella’s Garden by Glenda Millard and Rebecca Cool. The tale itself is cumulative and such a great fit to reinforce children’s memory recall as they are new to Auslan signs. Soon enough, signing was taking place everywhere, and the Gulamany children were confidently teaching each other, their older peers and family members how to sign the story with enthusiasm.

It seems clear that the Auslan learning has tapped into the complexity of the children’s narrative comprehension, which later results in their strong sense of confidence to pass on this emerging knowledge.

The Auslan teaching has started in many ways at our school. Our friend Meghan from Inner West Paediatrics inspired us to explore sign language as support for children with speech delay. For me, I would say a part of this teaching stems from my ongoing interest in finger play as an ‘old-school’ way of delivering a song or a story using metaphoric gestures.

This intentionality transferred into a considerate selection of Isabella’s Garden to begin using Auslan with, but this hasn’t limited our exploration to literature only. The children soon began asking how to sign things they encountered during the day. Whether we are on excursions or wandering in the garden, we continuously look up and build upon our current Auslan word bank. We listen to children’s interests and co-research with them to build our collective knowledge.

Co-constructing and de-constructing are central to our practice. Very often we ask children questions such as, “If this is yellow [signing], and this is house [signing], then guess what I’m saying? [signing both]” This fosters the children’s capacity to analyse and hypothesise. One of the most challenging signs is ‘tree’ which requires both arms to sign. To support children’s internalisation, we break down the signs according to our own interpretation, “So this is the ground [one arm laying flat], then comes the trunk [the other arm erecting on top of the ground], then blooms the leaves [hand on top swaying].”

My recent conversation with Dr Austin has reinforced our current strategies in teaching Auslan to our 2–3-year-olds. This work has inspired us to reflect on the growth of our curriculum, in which the children have led us to gain a much deeper understanding of what the world means to them through the lens of “two hands and a tale”.

Linh is an early childhood teacher at Explore & Develop Annandale she has an interest in how 2 to 3 years olds learn, young children’s citizenship and how they connect to nature.

Austin E. E., Sweller N. (2014). Presentation and production: The role of gesture in spatial communication. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 122(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2013.12.008

Austin E. E., Sweller N. (2017). Getting to the elephants: Gesture and preschoolers’ comprehension of route direction information. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 163, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.05.016

Dargue, N., & Sweller, N. (2020). Learning stories through gesture: gesture’s effects on child and adult narrative comprehension. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09505-0

Dargue, N., & Sweller, N. (2020). Two hands and a tale: when gestures benefit adult narrative comprehension. Learning and Instruction, 68, 1-13. [101331]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101331

Hupp J. M., Gingras M. C. (2016). The role of gesture meaningfulness in word learning. Gesture, 15(3), 340–356. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.15.3.04hup

Macoun A., Sweller N. (2016). Listening and watching: The effects of observing gesture on preschoolers’ narrative comprehension. Cognitive Development, 40, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2016.08.005

McKern, N., Dargue, N., Sweller, N., Sekine, K., & Austin, E. (2021). Lending a hand to storytelling: Gesture’s effects on narrative comprehension moderated by task difficulty and cognitive ability. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74(10), 1791–1805. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470218211024913